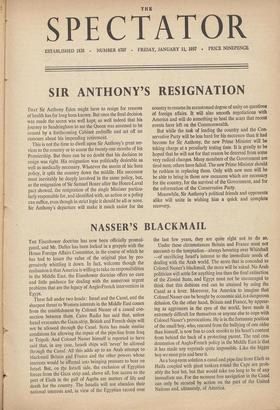

NASSER'S BLACKMAIL

THE Eisenhower doctrine has now been officially promul- gated, and Mr. Dulles has been locked in a grapple with the House Foreign Affairs Committee, in the course of which he has had to lessen the value of the original plan by pro- gressively whittling it down. In fact, welcome though the realisation is that America is willing to take on responsibilities in the Middle East, the Eisenhower doctrine offers no cure and little guidance for dealing with the numerous urgent problems that are the legacy of Anglo-French intervention in Egypt.

These fall under two heads : Israel and the Canal, and the sharpest threat to Western interests in the Middle East comes from the establishment by Colonel Nasser of a causal con- nection between them. Cairo Radio has said that, unless Israel evacuates the Gaza.strip, British and French ships will not be allowed through the Canal. Syria has made similar conditions for allowing the repair of the pipe-line from Iraq to Tripoli. And Colonel Nasser himself is reported to have said that, in any case, Israeli ships will 'never' be allowed through the Canal. All this adds up to an Arab attempt to blackmail Britain and France and the other powers whose interests would be affected into bringing pressure to bear on Israel. But, on the Israeli side, the exclusion of Egyptian forces from the Gaza strip and, above all, free access to the port of Elath in the gulf of Aqaba are matters of life and death for the country. The Israelis will not abandon their national interests and, in view of the Egyptian record over the last few years, they are quite right not to do so.

Under these circumstances Britain and France must not succumb to the temptation—always hovering over Whitehall —of sacrificing Israel's interest to the immediate needs of dealing with the Arab world. The more that is conceded to Colonel Nasser's blackmail, the more will be asked. No Arab politician will settle for anything less than the final extinction of the Zionist State, and Egypt must not be encouraged to think that this dubious end can be attained by using the Canal as a lever. Moreover, for America to imagine that Colonel Nasser can be bought by economic aid, is a dangerous delusion. On the other hand, Britain and France, by appear- ing as aggressors in the eyes of the world, have made it extremely difficult for themselves or anyone else to cope with Colonel Nasser's provocations. He is in the fortunate position of the small boy, who, rescued from the bullying of one older than himself, is now free to cock snooks to his heart's content from behind the back of a protecting parent. The real con- demnation of Anglo-French policy in the Middle East is that it has made any reprisals quite impossible. Like the bigger boy we must grin and bear it.

As a long-term solution a canal and pipe-line from Elath to Haifa coupled with giant tankers round the Cape are prob- ably the best bet, but that would take too long to be of any immediate use. For the moment free navigation in the Canal can only be secured by action on the part of the United Nations and, ultimately, of America. The arrival of a UN force in the Canal zone and the Sinai desert was, no doubt, a considerable step forward as far as the technique of settlement of international disputes goes, but it will only be a real step forward if it does produce a settle- ment. Simply to hold the Arab-Israeli dispute in permanent and artificial suspension, as the truce has done up to now, would be worse than useless. The danger of purely negative international action is that it prevents history, from taking its course. If in 1948 one side or other had actually won the Arab-Israeli war, the Middle East would be far more stable today. As it was, efforts were exerted to keep the combatants apart, but almost nothing was done to make them come to an agreement—which would have meant a recogni- tion by the Arab States of Israel's right to exist. UN observers proved quite ineffective to prevent the activities of fedayeen from Egypt and Jordan which could always be disowned by the governments concerned, while Israeli reprisals— which necessarily took the form of the type of full-scale punitive raid familiar on the NW frontier of India—were the subject of stern moral disapproval. In the Sinai desert the presence of UN forces may curtail action by the fedayeen, but, unless Egyptian provocation can be elimi- nated, General Burns and his troops will not merely be failing to do their job properly.' Given Egypt's military inferiority, they will also be tak- ing sides in a dispute in which they are bound to neutrality. The fedayeen raids are, after all, acts of war, and, if the UN Command is unable to prevent them, it should certainly not interfere with such steps as the Israeli Government itself sees fit to take.

This, in fact, is the testing time of the UN. If, during negotiations on the Suez Canal—and Colonel Nasser has said that he will only nego- tiate with Britain and France through the UN— it proves to be the case that Egypt can defy inter- national law as well as the West, then it is prob- able that the UN will lose what remains of a prestige that has already been badly shaken over Hungary. Because, as far as concerns the Anglo- French intervention, Colonel Nasser was sinned against, that is no reason why he should spend the rest of his life in sinning. That he has got the Canal is only too clear, but it is no part of• the purpose of an international police force to allow Egypt, a State that has just given striking proof of military incapacity, to blackmail Israel and the West from behind its shield. Any suggestion that this was the case would be highly damaging to the very idea of international organisations as arbiters of such disputes. It might even end by destroying it altogether. If the debate over the Eisenhower doctrine brings this danger home to America policy-makers, it will have done some good. For both America and the UN firmness and equity arc the only possible way of dealing with the problems presented by militant Arab nationalism.

Previous page

Previous page