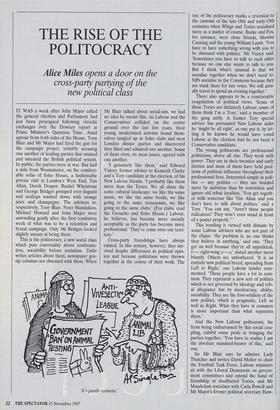

THE RISE OF THE POLITOCRACY

Alice Miles opens a door on the

cross party partying of the new political class

IT WAS a week after John Major called the general election and Parliament had just been prorogued following vitriolic exchanges over the Downey report at Prime Minister's Question Time. Amid uproar from both sides of the House, Tony Blair and Mr Major had fired the gun for the campaign proper, irritably accusing one another of leading parties that stained and smeared the British political system. In public, the parties were at war. But half a mile from Westminster, on the comfort- able sofas of Soho House, a fashionable private club in London's West End, Tim Allan, Derek Draper, Rachel Whetstone and George Bridges gossiped over linguini and scallops washed down with orange juice and champagne. The advisers to, respectively, Tony Blair, Peter Mandelson, Michael Howard and John Major were unwinding gently after the first combative week of what was to be a relentless and brutal campaign. Only Mr Bridges looked slightly uneasy at being there.

This is the politocracy, a new social class which puts conviviality above confronta- tion, sociability before socialism. Tatler writes articles about them, newspaper gos- sip columns are obsessed with them. When Mr Blair talked about social-ism, we had no idea he meant this. As Labour and the Conservatives collided on the centre ground over the last few years, their young, modernised activists found them- selves tangled up in Soho clubs and west London dinner parties and discovered they liked and admired one another. Some of them even, on most issues, agreed with one another.

`I genuinely like them,' said Edward Vaizey, former adviser to Kenneth Clarke and a Tory candidate at the election, of his New Labour friends. 'I probably like them more than the Tories. We all share the some cultural landscape: we like the same music, we like the same books, we like going to the same restaurants, we like going to the same clubs.' (For clubs, read the Groucho and Soho House.) Labour, he believes, has become more socially acceptable as the party has become more professional: 'They've come onto our terri- tory.'

Cross-party friendships have always existed. In this century, however, they sur- vived despite differences in political opin- ion and because politicians were thrown together in the course of their work. The 'It's purely cosmetic.' rise of the politocracy marks a reversion to the customs of the late-18th and early-19th centuries when Whigs and Tories socialised more as a matter of course. Burke and Fox, for instance, were close friends, likewise Canning and the young William Lamb. 'You have to have something wrong with you to be obsessed with politics,' Mr Vaizey said. `Sometimes you have to talk to each other because no one else wants to talk to you. But I think what's unusual is that we socialise together when we don't need to. MPs socialise in the Commons because they are stuck there for late votes. We will actu- ally travel to spend an evening together.'

There also appears to be a comfortable coagulation of political views. 'Some of these Tories are definitely Labour; some of them think I'm a Tory,' said a member of the gang airily. A former Tory special adviser has persuaded New Labour aides he 'might be all right', as one put it, by let- ting it be known he would have voted Labour at the election had he not been a Conservative candidate.

The young politocrats are professional politicians, above all else. They work with power. They are in their twenties and early thirties and most of them have held posi- tions of political influence throughout their professional lives. Interested simply in poli- tics — any politics — they are bonded more by ambition than by conviction and ignore old tribal loyalties. 'You get togeth- er with someone like Tim Allan and you don't have to talk about politics,' said a Tory. 'You can say, "Aren't these people ridiculous? They won't even stand in front of a poster properly." ' This bonding is viewed with distaste by some Labour advisers who are not part of the clique: 'the problem is, no one thinks they believe in anything,' said one. 'They get on well because they're all unpolitical, f— right-wing c—s,' stated another more bluntly. Others are unbothered. 'It is an entirely new political breed, spreading from Left to Right,' one Labour insider com- mented. 'These people have a lot in com- mon. They represent a new sort of politics which is not governed by ideology and trib- al allegiance but by meritocracy, ability, sociability. They are the foot-soldiers of the new politics, which is pragmatic, Left as well as Right. What they have in common is more important than what separates them.'

And the New Labour politocrats, far from being embarrassed by this social cou- pling, exhibit some pride in bringing the parties together. 'You have to realise I am the absolute standard-bearer of this,' said one.

So Mr Blair says he admires Lady Thatcher and invites David Mellor to chair the Football Task Force, Labour ministers sit with the Liberal Democrats on govern- ment committees and extend the hand of friendship to disaffected Tories, and Mr Mandelson socialises with Carla Powell and Mr Major's former political secretary How- ell James. And on any day of the week, in Westminster restaurants and west London dinner parties, one can find Mr Blair's press officer, Tim Allan, lunching with for- mer Tory special advisers Peter Barnes or David Cameron; Mr Mandelson's aide, Benjamin Wegg-Prosser, dining with Mr Hague's political secretary, George Osborne, or with Mr Vaizey; Mr Draper in the Groucho Club with Steve Hilton, the man responsible for the Tories' demon eyes' and tax bombshell campaigns, or even on holiday in the hills of Tuscany with the Liberal Democrat director of communica- tions, Jane Bonham-Carter.

When Jack Straw's special adviser, Ed Owen, arrived at his desk at the Home Office after the election, he found a long note from his Tory former opponent, Rachel Whetstone, giving him tips on how to handle the civil service.

The friendships can throw up the odd dilemma. One Labour aide remembers leaning out of the window at a drinks party at a Tory adviser's house, briefing newspa- pers against his hosts on his mobile phone. And Tim Allan went to a party thrown by Steve Hilton in the run-up to the election, on a Saturday night when the Observer was splashing a secret tape leaked to the Labour party on which Mr Hilton privately described Mr Major as a wimp. Mr Hilton knew that Mr Allan had been involved in leaking the tape. 'When Tim arrived, Steve simply shrugged and said, "work is work",' said another guest. Later in the evening, Mr Allan advised Mr Hilton how to get rid of a Sunday Mirror photographer who was waiting outside the house.

However, those Tories who believe that they have found soul-mates may be head- ing for a rude awakening. 'New Labour is more tribal than many people like me think,' one discovered. 'It's easy to under- estimate how committed they are to the New Labour project: if you ask them, they are definitely on one side. There are those who believe someone like Benjamin Wegg- Prosser is on no particular side. That's a mistake.'

One New Labour politocrat agreed. 'I sort of like them,' he said dismissively of the Tories he socialises with. 'I find them interesting and entertaining and good Company, but I don't like their values. We have shared encounters and experiences, but there's a difference between being entertained by someone and being their friend.'

Another added, 'When we were in oppo- sition, the Tories were so fractious that there was a fair bit of gossip we got from them that was rather useful, whereas they didn't demand any information from us. Now I am very careful. I would never say anything to any of them that I wouldn't say to a journalist from the Sun. I have never ever given them any information at all.' Call them Conservative, call them Labour, call them 'right-wing c—s'; they are soon coming to a dinner party near you.

Previous page

Previous page