Exhibitions 1

Wake or celebration?

Martin Gayford

This, or possibly next, year marks the 500th anniversary of Hans Holbein's birth. It isn't quite clear whether he was born in 1497 or 1498, an ambiguity quite common with artists born so long ago. Either way, one would have thought that a big exhibi- tion was in order — given Holbein's key position in English art and history. To date, however, the best we have managed is one of the National Gallery's pedagogic little exhibitions: Making and Meaning: Holbein's Ambassadors (sponsored by Esso), which looks in detail at the physical and symbolic construction of one great picture.

Viewed as a Holbein show this is not enough, but something to be going on with. Considered as a vindication of the National Gallery's cleaning policy, it has been denounced by my colleague Richard Dor- ment in the Daily Telegraph as 'outrageous': `A show which brazenly documents the way in which this famous and loved painting has been destroyed by its recent cleaning.' I half agree, and if Dorment is even partly right this show is more of a wake than a quincen- tenary celebration.

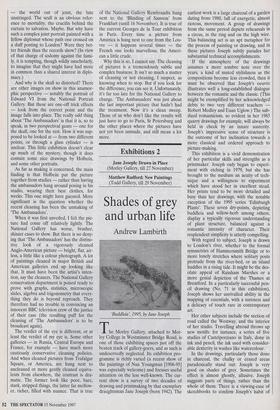

`The Ambassadors' is Holbein's largest and most ambitious surviving work as a portraitist — and also a strikingly peculiar painting. There are several mysteries about it, none of which is entirely cleared up by this exhibition or the accompanying book. In the 19th century it was unknown who the subjects were, but that problem has been solved to general satisfaction. They are two young French diplomats, Jean de Dinteville, on the left, and the Bishop of Lavaur, Georges de Selve. Dinteville did several spells as French ambassador to Henry VIII, the first in 1533, during which — like many Frenchmen exiled to Angleterre — he was browned off. 'I am,' he wrote, 'the most melancholy, weary and wearisome ambassador that ever was.'

Dinteville was cheered up, it seems, only by the advent of de Selve, perhaps on another secret diplomatic mission: 'Mon- sieur de Lavaur did me the honour of com- ing to see me, which was no small pleasure to me.' His reaction to this visit, it seems, was to commission a large, elaborate and presumably expensive portrait of the two of them from Holbein, over two square metres in size, with a skull in violent per- spectival distortion spread across the bot- tom of it and an array of musical, astronomical, geographical and horological instruments in the middle.

It seems a little odd. But the Dintevilles were a rum lot, with distinctly oddball ideas about portraiture. There were four broth- ers, one of whom was accused of poisoning the dauphin a few years later — a charge which did not stick. Subsequently, another fled from court accused of sodomy. In their chateau at Polisy, there was a group por- trait of the Dintevilles, perhaps the pen- dant of The Ambassadors', as Moses, Aaron and onlookers before the Pharaoh. Later in life, Jean de Dinteville had himself painted as St George — quite why no one knows — in a jolly mannerist picture in the exhibition.

The official explanation is that the splen- did clutter of instruments perhaps allude to the diplomatic troubles of the Reformation Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve ('The Ambassadors') by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1533, at the National Gallery — the world out of joint, the lute unstringed. The scull is an obvious refer- ence to mortality, the crucifix behind the curtain to salvation. Maybe. But why have such a complex joint portrait painted with a fellow diplomat whose path one crossed on a duff posting to London? Were they bet- ter friends than the records show? (In view of that charge of sodomy against the fami- ly, it is tempting, though wildly unscholarly, to imagine that they might have had more in common than a shared interest in diplo- macy.) And why is the skull so distorted? There are other images on show in this anamor- phic perspective — notably the portrait of Edward VI from the National Portrait Gallery. But these are one-off trick effects — look from the correct point and the image falls into place. The really odd thing about 'The Ambassadors' is that it is, so to speak, in two perspectival gears — one for the skull, one for the rest. How it was sup- posed to be looked at — from two different points, or through a glass cylinder — is unclear. This little exhibition doesn't clear up much of the mystery, though it does contain some nice drawings by Holbein, and some other portraits.

As far as making is concerned, the main finding is that Holbein put the picture together from studies — rather than having the ambassadors hang around posing in his studio, wearing their best clothes, for weeks. This one might have guessed. More significant is the question whether the recent cleaning has been the unmaking of `The Ambassadors'.

When it was first unveiled, I felt the pic- ture had come off relatively lightly. The National Gallery has worse, brasher, shinier cases to show. But there is no deny- ing that 'The Ambassadors' has the distinc- tive look of a vigorously cleaned Anglo-American picture — bright, flat, air- less, a little like a colour photograph. A lot of paintings cleaned in major British and American galleries end up looking like that. It must have been the artist's inten- tion, say the cleaners. The National Gallery conservation department is poised ready to prove with graphs, statistics, microscopic slides, algebra and trigonometry that every- thing they do is beyond reproach. They therefore had no trouble in convincing an innocent BBC television crew of the justice of their case (the resulting puff for the cleaning of 'The Ambassadors' is to be broadcast again).

The verdict of the eye is different, or at least the verdict of my eye is. Some other galleries — in Russia, Central Europe and France, for example — have much more cautiously conservative cleaning policies. And when cleaned pictures from Trafalgar Square, or America, are hung next to uncleaned or more gently cleaned equiva- lents from elsewhere, the contrast is dra- matic. The former look like poor, bare, stark, stripped things, the latter far mellow- er, richer, filled with nuance. That is true of the National Gallery Rembrandts hung next to the 'Blinding of Samson' from Frankfurt (until 16 November). It is true of the current Georges de la Tour exhibition in Paris. Every time a picture from America is hung next to one from the Lou- vre — it happens several times — the French one looks marvellous, the Ameri- can a little crude.

Why this is so, I cannot say. The cleaning of pictures is a tremendously subtle and complex business. It isn't so much a matter of cleaning or not cleaning, I suspect, as knowing when to stop. But if you look for the difference, you can see it. Unfortunately, it's far too late for the National Gallery to change. 'The Ambassadors' was just about the last important picture that hadn't had the treatment. Now it's a clean sweep. Those of us who don't like the results will just have to go to Paris, St Petersburg and the other places where the pictures have not yet been unmade, and still mean a lot more.

Previous page

Previous page