The Puff and the Book

By R. H. LANGBRIDGE IT has been said with some truth that publishers' advertisements are seen only by people with an interest in books. This is, of course, true of all forms of advertising; the public sees what it wants to see and ignores the rest, and as book-lovers account for a relatively small proportion of the total population, publishers' advertisements can have a strictly limited impact. Yet the history of book advertising is as old as advertising itself. Books and patent medicines were certainly among the first articles to be announced in the press.

In the very early days all advertising was set in the same type as the matter in the editorial columns. Even a hundred years ago announcements seldom amounted to more than four or five lines of small type set in single-column form. Since 'displayed' (large type) advertisements became general early this century the other announcements have been known as 'classifieds.'

A typical example of a publishers' classified announcement. taken from The Times of 1856, ran as follows : The New Novel—now ready at all libraries, 3 vols. THE HOUSE Of mime.: A Family History. 'The story will be read with unflagging interest. The characters are power- fully drawn.'—Literary Gazette. 'A splendid production.'— John Bull. Hurst & Blackett, publishers, successors to Henry

Colburn.

This style of advertisement continued practically unchanged for the next thirty years until someone, possibly a publisher, conceived the idea of repeating the key line of his announcement. To our eyes the difference is trifling, but when

THE HOUSE OF ELMORE

became

THE HOUSE OF ELMORE THE HOUSE OF ELMORE THE HOUSE OF ELMORE

the seeds were sown from which has blossomed the exotic flowers of all present-day 'displayed' advertising. This par- ticular 'gimmick' could be carried to the point of absurdity. One Duckworth page announcing a new novel by E. Temple Thurston repeated the title of the book seventy-one times.

It is difficult to use much originality in advertising books and a few well-tried ideas have been in constant use for many years. But if the structure of publishers' advertisements has remained virtually unaltered there have been considerable fluctuations in the media used to announce new books. Fifty years ago it was inconceivable that anyone would buy the Observer or Sunday Times for their book reviews. Occasional reviews did appear from week to week, but there was no regular feature as there is today. It was the weekly journals of opinion that specialised in books. The pages of the Spectator, Atheneum, Nation and Saturday Review were crowded with reviews and publishers' advertisements. The daily papers were also literary-minded. The Morning Post, Daily Chronicle, Daily Telegraph and Daily News gave many columns of book reviews each week, and these were supported by book adver- tisements. The Times was, as usual, in a class by itself. Reviews scarcely ever appeared in its pages, but several columns of book advertisements were carried each week. Book reviews were printed in the eight-page Times Literary Supplement, issued free with The Times.

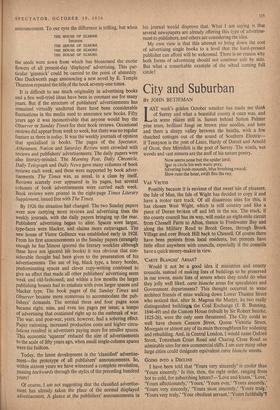

By 1926 the situation had changed. The two Sunday papers were now carrying more reviews and advertising than the weekly journals, with the daily papers bringing up the rear. Publishers' advertising began to alter. Spaces were larger, type-faces were blacker, and claims more extravagant. The new house of Victor Gollancz was established early in 1928. From his first announcements in the Sunday papers (strangely enough he has ilmost ignored the literary weeklies although these have not ignored his books) it was obvious that con- siderable thought had been given to the presentation of his advertisements. The use of big, black type, a heavy border, predominating spaces and clever copy-writing combined to give an effect that made all other publishers' advertising seem weak and old-fashioned; and within a few months the larger Publishing houses had to retaliate with even larger spaces and blacker type. The book pages of the Sunday Times and Observer became more numerous to accommodate the pub- lishers' demands. The normal three and four pages soon became eight, nine, and even ten pages per issue; a tempo of advertising that continued right up to the outbreak of war. The war, and post-war, years, however, had a sobering effect. Paper rationing, increased production costs and higher circu- lations resulted in advertisers paying more for smaller spaces. This economic 'squeeze' reduced the size of advertisements to the scale of fifty years ago, when small single-column spaces were the fashion.

Today, the latest development is the 'classified' advertise- ment—the prototype of all publishers' announcements. So, within sixteen years we have witnessed a complete revolution, passing backwards through the styles of the preceding hundred years! .

Of course, I am not suggesting that the classified advertise- ment has already taken the place of the normal displayed advertisement. A glance at the publishers' announcements in his journal would disprove that. What 1 and saying is that several newspapers are already offering this type of advertise- ment to publishers, and others are considering the idea.

My own view is that this attempt to bring down the cost of advertising single books to a level that the hard-pressed publisher can afford will be welcomed. There is no reason why both forms of advertising should not continue side by side. But what a remarkable example of the wheel coming full circle!

Previous page

Previous page